There was a time in my life, not very long ago, when I had to choose what I wanted to pursue as my majors in college. Considering the sustained interest I had had in it since childhood and the substantial exposure I got during the course of my schooling, history became my first choice. The verdict had been made and a timely notice was sent to my parental authorities. Though I ended up choosing a completely different discipline for my under-grad (a story which we shall save for the coffee table), this decision had put me in close proximity to a certain attitude people held towards History, both as an academic discipline and as a body of knowledge that informs our lives.

Two subsequent instances came to me as an eye opener. The first was when an aunt of mine visited us. After she was done with the obligatory exchanges of greetings and enquiries, she asked me about what I was planning to do in college. The moment she heard my reply, without a split second delay, she said - “History?…What will you do for food then?”. I thought I was being funny in replying “I don’t know! Eat, probably?”. I don’t think she thought the same.

The second was when I was talking to a statistician. At some point in our conversation he enquired about my plans for undergrad. His response to it was much more than a cynical comment. “History? Why would you do that? Its for people who are practically jobless. Why would you do that? What is the point of such a study anyways? We all like to paint our pasts with our own colours that we like. We all do that anyways. Why waste time, effort and money studying it? It has no practical usage in any of our lives. What’s the point?”. After that, he went on to narrate the details of some unsolved murder and rape cases filed against some well-known politicians and said “we cannot find out what the truth is in instances that happen very much in the present. How can we be sure of something that happened a thousand years ago?”. It is interesting to note that, in his head, these comments were very much within the bounds of social niceties.

The fact that I am writing this after almost four years is itself a testimony to the lasting impact these instances had on me. Not only did I feel personally intimidated and invalidated, but also a great compulsion of curiosity to ponder over the relevance of such a body of knowledge in our lives. What is history? Why should one study it? What is the point of studying history? I commenced my thinking from the very foundations.

Questions regarding the usefulness of understanding history often yields us the following answers:

- Learning history helps us

- Learn from past mistakes so as to not repeat it

- Learn from past examples and make ourselves better

- Acquire a sense of direction by understanding where we come from

- Trace our roots and get a sense of grounding

All these answers seem to lie within the presumption of history being the study of our past. But, what is the past? Whatever that precedes the present is the past and whatever that succeeds it is the future. Then, what is the present? The nature of the flow of time seems to be such that we can never point to one particular moment and call it the present (unless we could freeze time). Like how Aristotle put it in his famous riddle of time that goes something like -

“We think about time as divided into the past, present and future. What is the present? How thick is it? The present is just a limit between the past and the future. The past is something that does not exist. It has existed, but it does not exist any longer. The future is something that does not exist. It will exist, but it does not exist. And the present is nothing. So time seems to be nothing dividing something non-existent from something non-existent”

If that is the case, what then is the point of the notion of thinking about time in terms of the past, present and future? Where does the past end and the present begin? With that being unclear, what is the past that history claims to study?

With these questions running in my mind, I was once looking at the night sky from my terrace (a practice that was once part of my routine). Almost out of nowhere, I realized the obvious implications of a fact that I had known for very long. The stars that I was seeing in the sky were not only from different points in space, but also from different points in time.

Since light travels at a finite speed, it takes a certain duration to travel the distance between the star and the pupil of my eye. Since each star is situated in varying distances from the earth, the time light takes to travel this distance also varies from star to star. So what appears to me as a star is an image of it from the past, relative to its distance from the earth. For instance, the star I see as Sirius is its light, eight years from the past. An interesting example is the star named Betelgeuse, which is a dying star. Light takes 643 years to reach earth from Betelgeuse. That means, that if the star explodes this very second, I will be able to see it in my night sky only after 643 years. If the star dies now, it will take me 643 years to know it.

Therefore, every time I am staring at the night sky, not only am I looking at different points in space, but also glimpsing into different points in time (in the past). This realization came to me as a revelation of the apparent and obvious nature of my perception of reality.

Not only is this the case with the stars, but also with the reality that I experience on a daily basis. Based on how close or how far I am from the objects that I see around me, I am glimpsing into various points in its past. Even if I am just a few millimetres away from some object, light takes some time, however negligible, to travel that distance and reach my eye. This means that I am incapable of experiencing the present. Rather, what I experience to be my present, is based on my relative position, a conglomeration of various events from the past.

Therefore, what each of us experience to be our present reality is actually a unique picture woven out of various threads from the past, coming together in our relative position to it. In that case, our attempts to understand the present is but an attempt to understand various pasts uniting at our point of vantage. If I have to sum it up optimistically - “what we experience to be the present is nothing but various events from the past coming together at the point where we stand to view it”. And pessimistically - “our attempts to perceive and experience reality is forever bound to the past. We are inherently incapable of experiencing the present”.

Either way, it is evident that our present reality is a relative coming together of various pasts. In that case, the present is no longer the limit between the past and the future, but the past we see from our point of apprehension.

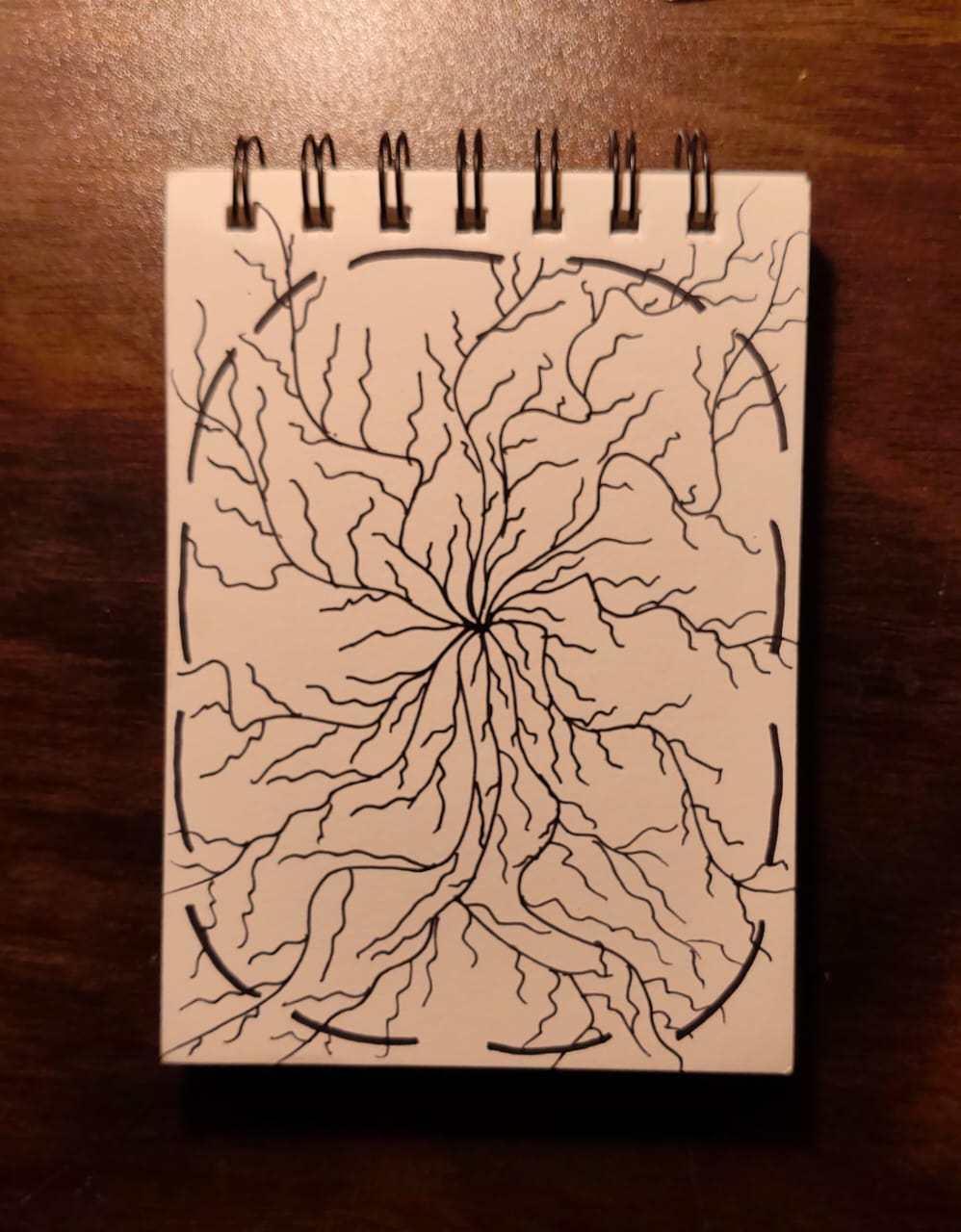

The night that the stars taught me this, was the night when history was no longer the study of the past for me. It is the study of my present, which is nothing but the coming together of various pasts. It is a body of knowledge that informs my innate striving to comprehend the various threads from the past that weave together, the garb of my present. The furthering of this comprehension directly results in the heightening of my awareness of the present reality. It is like viewing the night sky and trying to see a thread of light from each star reach the pupil of my eye. Some of these threads extend in time much longer than I do. They are stretched across longer spans of time and carry the essence of the star with it. The possibility of it showing me something in my reality that I haven’t yet seen is what keeps my curiosity for history alive forever.

In that case, can the complete comprehension of history move us towards an awareness of total reality? The answer is, no. Like how light from some stars never reaches the earth and our eyes are incapable of perceiving certain rays emitted by celestial bodies, events from the past that we cannot see from our relative position in the present will forever remain out of our bounds of knowledge. Even if these events constitute a big portion of our present reality and actively impact our lives, we can still have no knowledge of it. The fact that our apprehension of reality is relative to our points of perception, is against our claim to any ultimate knowledge.

These answers to the questions of intent, purpose and usefulness of understanding history seemed valid. It remained valid until the day my father showed me a newspaper article. It was about the success of a solar mission satellite. The article displayed the first photograph of the sun clicked by the satellite, alongside the picture of the sun as we see it in our sky. As anticipated, there was an apparent difference in the colour and details between the two photographs. The reason for the difference was the obvious interference of the ozone layer in the latter picture.

As I looked at the article, I had a daunting realization of another obvious fact. The same object viewed from different points makes it appear to be completely different things. The appearance of reality not only seems to change in each point of view, but also due to the tools of perception and the nature of things that interfere with our vision. If a cow, a snake and I view the same thing, it is going to appear differently to each, due to the nature of the tool we use to see it. How sure can we be that two human beings viewing the same thing are actually seeing the same thing? How sure can I be that the green I see is actually the green you see? What if we are just associating the same object with the colour, but actually seeing different things?

So, it is evident that the nature of reality that we experience is not only relative to our points of view, but also tainted by the tool that we use to apprehend it and other interferences in our perception. These taints are counted as biases in history. If our view of reality is forever bound to our relative points of view and tainted by the nature of our tools of apprehension, can there ever be an unbiased view of history? If yes, how? If not, can our knowledge of history count as truth?